Snap analysis: Spring Statement 2025

Director

“The economic and fiscal outlook has become more challenging since the Autumn Budget”, begins the executive summary of the OBR’s ‘Economic and fiscal outlook’. You don’t say. “Outturn data and indicators of business, consumer and market sentiment have, on balance, been negative for the economic outlook”.

The result is a halving of the growth forecast this year, and downward revisions to both cumulative growth and productivity levels by 2029. Borrowing and debt are both forecast to be higher at the end of the decade.

Next year, however, the OBR forecasts a heroic recovery in growth to 1.9% (the external average forecast is 1.3%). Growth has also been revised up slightly in subsequent years. Real Household Disposable Income per person growth is slightly higher than forecast in October — however government measures lower RHDI per person.

It is, however, worth noting that while the OBR is expecting a profit and business investment recovery, they have also been unable to score any impact from the Government’s ‘Plan to Make Work Pay’ — the employment rights reforms — “as there is not yet sufficient detail or clarity about the final policy parameters”. Which feels rather important. That said, some of the supply-side effects of the welfare reforms have also not been scored.

The Chancellor has taken action to recover her ‘fiscal headroom’ (predictably wiped out due to the “challenging” times). After measures to cut spending (largely welfare, international aid and lower departmental spending increases, and 15% reduction in the cost of administering government) and recover more tax, we’re weirdly back at exactly the same 2029-30 ‘headroom’: £9.9 billion.

That paper-thin margin looks as convincing as it did in October — and the OBR are once again very clear that the level of uncertainty is very high. In fact they explicitly state its 50:50 whether the mandate will be met (well, a 54% chance).

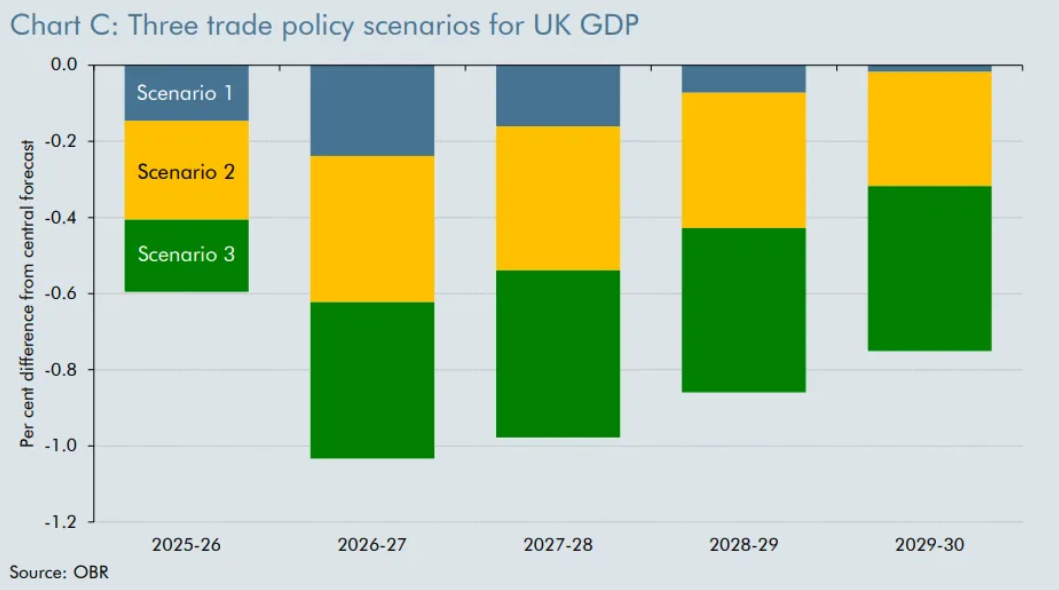

As we head towards tariff day on April 2, I will leave you with this nugget of a sentence from page 45, followed by a graph: “our central forecast does not explicitly account for the impact of recently announced tariff increases by the US and other countries.”

All eyes are now on June’s Spending Review when we’ll get the detail of the spending settlements. But regardless of what the SR says, it's hard to believe that the Chancellor won’t be back making further adjustments given the deeply uncertain global and domestic context.

Read on for the teams’ summary of the Chancellor’s key moves.

Welfare reform

As outlined in last week’s Green Paper, addressing the ballooning costs of disability and incapacity-related benefits is a key government focus. The proposed reforms deliver the lion’s share of the headroom recovery. It’s worth noting that the cuts are slowing the rate of growth not reversing it.

The biggest contributor is a tightening of eligibility for Personal Independence Payment (paid in or out of work), netting £3.5 billion. Halving the value of the incapacity-related payment in Universal Credit for new claimants, and then freezing its value for all, will save a further £1 billion.

At the same time, the Government is also increasing the UC standard allowance (costing £1.8 billion) and introducing more employment support (costing £1 billion).

Each of these policies will have a range of potential behavioural implications and the OBR states that the complexity of the interactions means impacts are “very uncertain”, in addition to lacking the detail to be able to model aspects of the reforms. It’s also the case that previous big reforms have failed to delivered the savings expected.

The changes will prove controversial, not least due the DWP’s impact assessment (also published today) suggesting they could lead to an additional 250,000 people, including 50,000 children, in relative poverty.

Investing in defence

The Government is fully funding its pledge to increase defence spending to 2.5% of GDP by 2027, and recommitting to increase it to 3% in the next parliament. The route to get there involves another £2.2 billion of spending next year, mostly capital investment, which the Government had already announced would be funded by reducing aid (ODA) spending to 0.3% of GNI.

But the welcome extra spending risks being swallowed entirely by the growing costs of Britain’s nuclear deterrent programmes, and replacing kit already sent to Ukraine.

More day-to-day spending (RDEL) to increase the tempo of joint exercises in Europe is good, but several divisions are not at fighting readiness because of kit shortages.

Urgent reform of procurement and industrial capacity is crucial. The newly-announced UK Defence Innovation Unit can definitely fill that role for R&D procurement of cutting-edge technologies like Directed Energy Weapons and AI. But they will need a plan on how to rebuild depleted stocks of conventional munitions. Changes to UK Export Finance’s (UKEF) lending rules to crowd in international demand might help build a more robust supply chain, but the Spending Review will need much more detail on how to build the industrial capacity to usefully spend this additional capital investment.

Transforming government

As part of her ‘spend now, save by the end of the forecast’ plans, the Chancellor announced a new ‘Transformation Fund’, aimed at unlocking around £3.5 billion in efficiencies by the end of the Parliament. This includes £225 million of policies announced in today’s Statement, and £3 billion to be allocated at the Spending Review.

The majority of this, £150 million, will be used for a much-trailed voluntary exit scheme, to cut the size of the civil service and so reduce “admin costs” by 15% (around £2 billion) by the end of the decade.

It’s positive government is being upfront about the cost of reducing headcount: as we argued two weeks ago, slimming down the civil service requires a serious plan, and serious cash for exit payments. And the Civil Service also remains well above its pre-pandemic, pre-Brexit size.

But it also really matters how this process is managed, and relying on voluntary redundancy programmes risks the most talented civil servants, with in-demand skills, taking the pay out. Instead, government must identify roles and teams that are not needed, and use compulsory redundancies to cut headcount.

Moves to invest in new foster home places, to reduce pressure on local authority-funded social care; in tech for probation officers, to cut down paperwork; and DSIT-led “frontier AI” pilots, to test and deploy new applications that could help boost efficiency across government, were all very welcome, productivity-friendly moves. However, they are together worth pennies (£75 million) in comparison to the overall Fund, and so we’ll wait on the Spending Review for detail on how the rest will be used.

Growth through planning reform

The Chancellor made much of the projected impact of recent changes to the English planning system, rightly noting their exceptional value given there has been no new spending. The OBR predicts that the changes will lead to 170,000 additional homes over the forecast period. That would be a serious contributor to growth, boosting GDP by 0.2% by the fifth year of the forecast and worth £6.8 billion overall. This is characterised by the OBR as a “modest” boost to the economy.

Reeves’ claim that the Government is now getting to within “touching distance” of its housebuilding pledges still feels implausible, though: their promise for 1.5 million homes in England by the end of the parliament (so… 2029) would require a huge turnaround at this point, given that lately the rate of new building has actually been falling.

Tackling tax avoidance and debt

The Government announced another slew of measures aimed at increasing tax compliance and debt collection. Chief among these are plans to hire additional HMRC staff and expand the use of private sector debt collection agencies. These are estimated to raise an additional £1 billion per year by 2029-30. This is on top of the projected additional £6.5 billion per year by 2029-30 raised through similar measures announced in the Autumn Budget.

The overall tax gap is estimated to be 4.8 per cent of total tax liabilities, and there is an estimated £147 billion of tax debt available for pursuit — more than double since pre-pandemic levels. That is a significant chunk of money which could be unlocked.

However, as the OBR politely acknowledges, “there remains significant uncertainty around the yield that will be generated from these measures”. Previously governments have consistently tried and failed to crack down on tax avoidance and evasion. Indeed, taken together the measures announced today and in the Autumn Budget are only predicted to reduce the tax gap by 0.4 percentage points.